The Shetland Islands lie 170km from Great Britain, the mainland of the UK. From the Scottish capital of Edinburgh, direct flights to the islands’ only airport cost at least £210 and take 90 minutes. Overnight ferries leave from Aberdeen, the country’s oil and gas hub, once a day.

When the boat docks at the islands’ largest town of Lerwick, you will find another community heavily influenced by fosill fuel extraction. The Shetland Islands lie at the physical centre of much of the UK’s offshore oil and gas extraction industry. As a result, using fossil fuels for power generation there has always made logical sense.

Gas turbines at a shipping petrochemical terminal compliment the main diesel-fuelled power station in Lerwick. Commissioned in 1953, this power station is now looking at the end of its life, and residents need a new solution. While some would assume renewables to be the next step, plans have faced steady opposition.

Shetland offers a huge opportunity to wind developers, as Shetland’s existing Burradale wind farm proves. Sited onshore on the largest island, Mainland, the five turbines generate 3.68MW with an average capacity factor of 52%. This measure of generating potential sits well above the UK average of 28%. At one point, Burradale generated the most energy per unit of installed capacity in the world.

British utility company SSE saw the opportunity and proposed a wind farm on the islands. In 2007, this merged with a proposal by the local council, forming the first plans for a 150-turbine wind farm. After an approval process and a change of plans, the Viking wind farm gained consent as a 103-turbine project making it the UK’s biggest onshore wind farm.

This reduction in the proposed number of turbines came partly from the planned location across the islands’ peat bogs. Peat bogs store significant amounts of carbon emissions, even more intensely than forests. Building works would disturb and release the trapped CO₂, and while the Viking managers say they will take measures to mitigate this, it has damaged the environmental credentials of the project in some eyes.

Apart from this, many rare species of plant and bird live in peat bogs. When the plans gained consent in April 2012, the developers quickly faced a court challenge over their wildlife impact assessments.

Meet at Intersolar Europe, June 14–16, 2023 MESSE MÜNCHEN

Meet at Intersolar Europe, June 14–16, 2023 MESSE MÜNCHEN

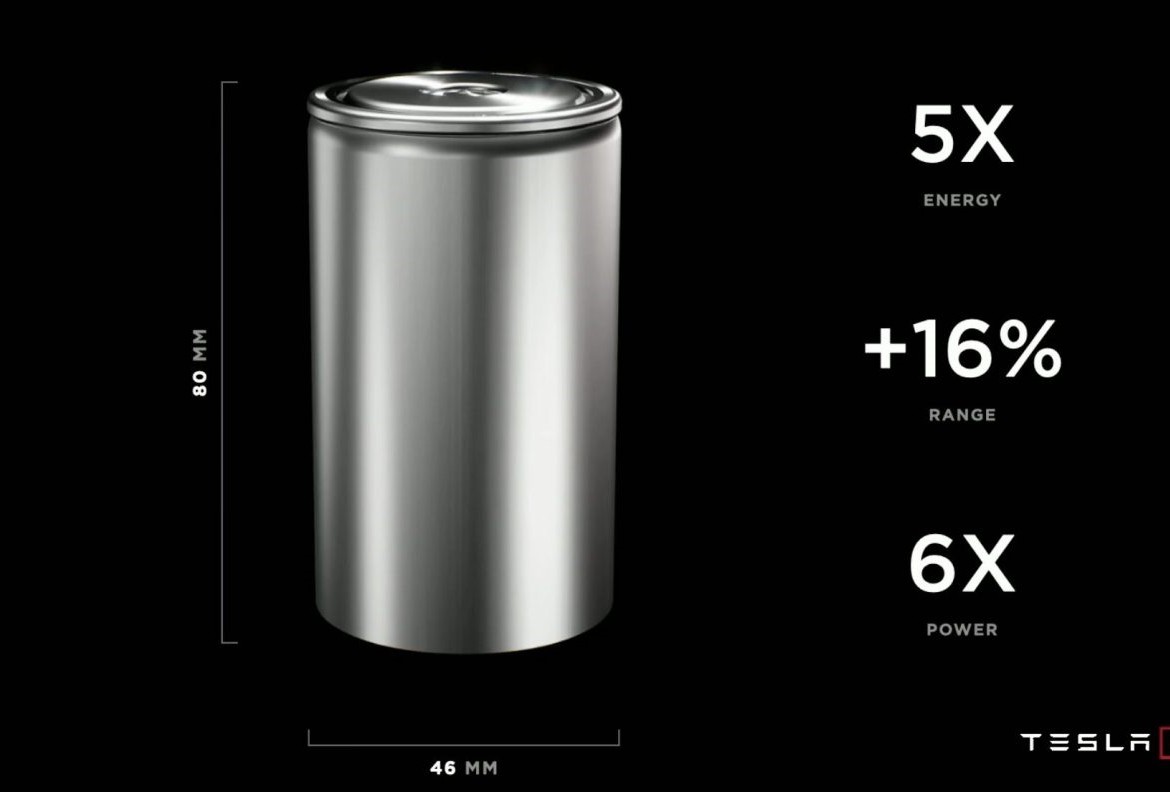

Tesla unveils new 4680 battery cell: bigger, 6x power, and 5x energy

Tesla unveils new 4680 battery cell: bigger, 6x power, and 5x energy

Next-generation batteries take major step toward commercial viability

Next-generation batteries take major step toward commercial viability

Dear Oil Executive, Is There A Lack Of Imagination?

Dear Oil Executive, Is There A Lack Of Imagination?